I explore the tension between the gifts of being my mother’s daughter and the cost of being emotionally shaped to please her.

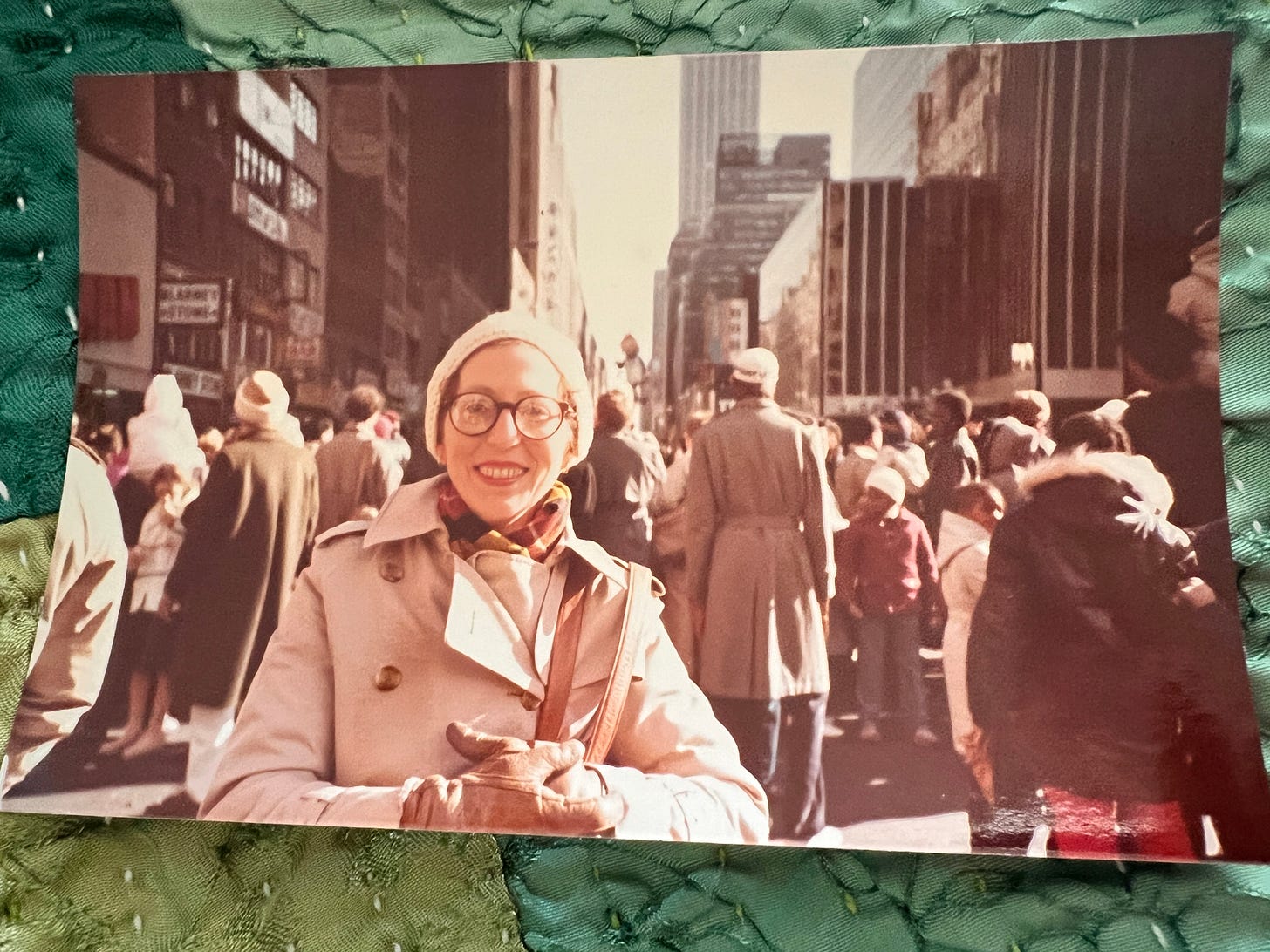

Later in her life she rarely traveled without my father, but in 1981 she came to visit me in New York for Thanksgiving, leaving the family at home in Birmingham, Alabama. We went to the Strand Bookstore, MOMA, the Morgan Library, and more. Wrapped in her wool-lined Burberry, she was eager to explore the city where I was an undergraduate at Barnard College. I was happy to be her guide - well, that’s not quite true. I feared her judgment and was a walking specimen of jangling nerves, navigating my desire to please her and to be her perfect daughter through the choppy and complicated truths of my evolving self. Still, I pulled on the red wool mittens that she had knitted for me, and the long red plaid Pendleton coat that she’d bought for me, and off we went to the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

In the narrative essay “Wool Mittens” that I completed recently, I explore the tension between the gifts of being my mother’s daughter and the cost of being emotionally shaped to please her. She gave me Edith Piaf, Louis Armstrong, Dylan Thomas, and Chopin. She gave me the Bayeux tapestries when she took me to The Cloisters. She gave me the journals of Anais Nin for Christmas when I was a young teen. My lifelong travel to archives and rare book libraries around the world stems from the exposure that she offered and her love of language. And to her dismay, although she never said it outright, I became a poet who worked a job to get by. That was not what she had in mind for her daughter. I knew that she was disappointed, so I worked doubly hard to make up for it as best I could. And finally, with the long-term psychological help of Dr. Patricia Honea-Fleming, I claimed my own life, mostly.

During Covid-19, when Alzheimer’s was claiming my mother more fully after a gradual movement across years, I began to consider the value of exploring my shadow relationship with Mother. What was the truth of my relationship with her beyond the romanticized version of being the daughter of my mother, who was a librarian at The Altamont School, an independent school in Birmingham, where she changed the lives of young people by putting books in their hands. And I’m off again to the business of putting her back on the pedestal. Beyond the pedestal, this is true, and the shadow is also true. This was the beginning of “Wool Mittens” which is the final piece in my new collection of poems “The Conjugation of Winter.”

In 1978 she sat across from me at the little kitchen table. I was sixteen, just back from my first trip to France, a school trip where I’d enjoyed the attention of young Gerard, our bus driver. We attended in all sorts of places - in the bus, in his hotel room, in a cathedral, on a bench in Rouen. When my teachers learned of the affair, Gerard was sent away, and a new, much older driver Serge took his place. I’d told my teachers that I was not under the sway of Gerard. I was simply having an authentic French experience. They feared that I would run away with him. This had never crossed my mind. Back at home in Mother’s kitchen, she tried to reach me. “I just hope that sex doesn’t become like shaking hands for you,” she said. “Mother, I assure you that it will not,” I replied. This was our conversation in full. What an opportunity for communication we missed that day and in the days and years that followed.

As I continue to explore my relationship with my mother, now that I am older than she was when she came to New York in 1981, I also explore my relationship with my son, my sole offspring, who lives in New York. I notice that as I dismantle the pedestals of relationship I begin to discern the mycelial reach of our connectedness, beyond good, bad, happy, or sad yet containing these as well as the shared dark underbelly where life collides, awareness blooms, and we manifest as beings. I am learning to speak the language of this place where we are born.